“From the last chapter the reader will recall Michael Rappengluck’s work on the zodiacal constellation of Taurus, depicted at Lascaux some 17,000 years ago as an auroch (ancient species of wild cattle) with the six visible stars of the Pleiades on its shoulder”.

Graham Hancock

Already I (Damien Mackey) touched upon some of Michael Rappengluck’s archaeoastronomical insights about the Lascaux cave depictions in the first of my multi-part series:

The date for Lascaux as given here by Graham Hancock in his book Magicians of the Gods (2015), I personally would consider to be thousands of years too early.

That same book I was reading - and generally enjoying - last night and came upon this section most relevant to my series and to the findings of Michael Rappengluck:

Neolithic puzzle

[Paul] Burley’s paper is entitled “Göbekli Tepe: Temples Communicating an Ancient Cosmic Geography.” He wrote it originally in June 2011 … in February 2013 he asked me to read his paper, which he said concerned “evidence of a zodiac on one of the pillars at Göbekli Tepe.” I read it, replied that I found it “very persuasive and interesting, with significant implications” ….

“Significant implications,” I now realize as I read through the paper again in my hotel room in ŞanlIurfa, was a huge understatement. But I didn’t make my first visit to Göbekli Tepe until September 2013 and by then, clearly, I’d forgotten the gist of Burley’s argument, which focuses almost exclusively on Enclosure D and on the very pillar, Pillar 43, that I’d been most interested in when I was there.

My interest in it had been sparked by Belmonte’s suggestion that the relief carving of a scorpion near its base (which the reader will recall was hidden by rubble that Schmidt refused to allow me to move) might be a representation of the zodiacal constellation of Scorpio. ….

Here’s where he gets to his point:

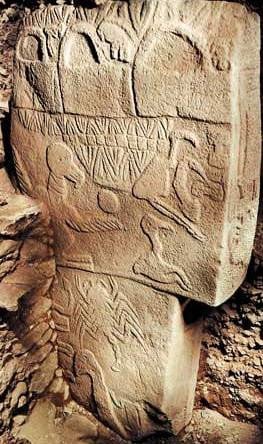

One of the limestone pillars [in Enclosure D] includes a scene in bas relief on the upper portion of one of its sides. There is a bird with outstretched wings, two smaller birds, a scorpion, a snake, a circle, and a number of wavy lines and cord-like features. At first glance this lithified menagerie appears to be simply a hodgepodge of animals and geometrical designs randomly placed to fill in the broad side of the pillar.

The key to unlocking this early Neolithic puzzle is the circle situated at the center of the scene. I am immediately reminded of the cosmic Father—the Sun. The next clues are the scorpion facing up toward the sun, and the large bird seemingly holding the sun upon its outstretched wing. In fact the sun figure appears to be located accurately on the ecliptic with respect to the familiar constellation of Scorpio, although the scorpion on the pillar occupies only the left portion, or head, of our modern conception of that constellation. As such the sun symbol is located as close to the galactic center as it can be on the ecliptic as it crosses the galactic plane.

….

Burley then presents a graphic that “illustrates the crossing of the galactic plane of the Milky Way near the center of the galaxy, with several familiar constellations nearby.” A second graphic shows the same view with the addition of the ancient constellations represented on the pillar:

Note that the outstretched wings, sun, bird legs and snake all appear to be oriented to emphasize the sun’s path along the ecliptic … The similarity of the bas relief to the crossing of the ecliptic and galactic equator at the center of the Milky Way is difficult to reject, supporting the possibility that humans recognized and documented the precession of the equinoxes thousands of years earlier than is generally accepted by scholars … Göbekli Tepe was built as a symbolic sphere communicating a very ancient understanding of world and cosmic geography. Why this knowledge was intentionally buried soon afterward remains a mystery.

….

As I sit in my hotel room in ŞanlIurfa in July 2014 spinning the skies on my computer screen, I’m coming more and more to the conclusion that Paul Burley has had a genius insight about the scene on Pillar 43 at Göbekli Tepe. Burley’s language in his paper is careful—almost diffident. As we saw in Chapter Fourteen, he says that “the sun figure appears to be located accurately on the ecliptic with respect to the familiar constellation of Scorpio.” He speaks of other “familiar constellations” nearby.

And he draws our attention to the large bird—the vulture—“seemingly holding the sun upon an outstretched wing.”

He does not say which constellation he believes the vulture represents, but the graphics he includes to reinforce his argument leave no room for doubt that he regards it as an ancient representation of the constellation of Sagittarius. ….

We’ve already seen that there is evidence for the identification of constellations going far back into the Ice Age, some of which were portrayed in those remote times in forms that are recognizable to us today.

From the last chapter the reader will recall Michael Rappengluck’s work on the zodiacal constellation of Taurus, depicted at Lascaux some 17,000 years ago as an auroch (ancient species of wild cattle) with the six visible stars of the Pleiades on its shoulder.

Acknowledging such surprising continuities in the ways that some constellations are depicted does not mean that all the constellations we are familiar with now have always been depicted in the same way by all cultures at all periods of history. This is very far from being the case. Constellations are subject to sometimes radical change depending on which imaginary figures different cultures choose to project upon the sky. For example, the Mesopotamian constellation of the Bull of Heaven and the modern constellation of Taurus share the Hyades cluster as the head, but in other respects are very different. …. Likewise the Mesopotamian constellation of the Bow and Arrow is built from stars in the constellations that we call Argo and Canis Major, with the star Sirius as the tip of the arrow. The Chinese also have a Bow and Arrow constellation built from pretty much the same stars but the arrow is shorter, with Sirius forming not the tip but the target. ….

Even when constellation boundaries remain the same from culture to culture, the ways in which those constellations are seen can be very different.

Thus the Ancient Egyptians knew the constellation that we call the Great Bear, but represented it as the foreleg of a bull. They saw the Little Bear (Ursa Minor) as a jackal. They depicted the zodiacal constellation of Cancer as a scarab beetle. The constellation of Draco, which we see as a dragon, was figured by the Ancient Egyptians as a hippopotamus with a crocodile on its back. ….

There can therefore be no objection in principle to the suggestion that the constellation we call Sagittarius, “the Archer”—and depict as a centaur man-horse hybrid holding a bow with arrow drawn—could have been seen by the builders of Göbekli Tepe as a vulture with outstretched wings.

I spend hours on Stellarium toggling back and forth between the sky of 9600 BC and the sky of our own epoch, focusing on the region between Sagittarius and Scorpio—the region Burley believes is depicted on Pillar 43—and looking at the relationship of the sun to these background constellations.

The first thing that becomes clear to me is that a vulture with outstretched wings makes a very good figure of Sagittarius; indeed it’s a much better, more intuitive and more obvious way to represent the central part of this constellation than the centaur/archer that we have inherited from the Mesopotamians and the Greeks. This central part of Sagittarius (minus the centaur’s legs and tail) happens to contain its brightest stars and forms an easily recognized asterism often called the “Teapot” by astronomers today—because it does resemble a modern teapot with a handle, a pointed lid and a spout. The handle and spout elements, however, could equally effectively be drawn as the outstretched wings of a vulture, while the pointed “lid” becomes the vulture’s neck and head.

It is the outstretched wing in front of the vulture—the spout of the teapot—that Burley sees as “holding the sun,” represented by the prominent disc in the middle of the scene on Pillar 43.

….

Figure 49: A vulture with outstretched wings makes a much better, more intuitive and more obvious way than an archer to represent the bright, central “Teapot” asterism within the constellation of Sagittarius.

….

….

But the vulture and the sun are only two aspects of the complex imagery of the pillar. Below and just a little to the right of the vulture is a scorpion.

Above and to the right of the vulture is a second large bird with a long sickle-shaped beak, and nestled close to this bird is a serpent with a large triangular head and its body coiled into a curve. A third bird, again with a hooked beak, but smaller, with the look of a chick, is placed below these two figures—again to the right of the vulture, indeed immediately to the right of its extended front wing. Below the scorpion is the head and long neck of a fourth bird. Beside the scorpion, rearing up, is another serpent.

Part of the reason for my growing confidence in Burley’s conclusion, though he makes little of it in his paper, is that these figures, with only minor adjustments, compare intriguingly with other constellations around the alleged Sagittarius/vulture figure.

First and foremost, there is the scorpion below and a little to the right of the vulture, which we’ve seen already has an obvious resemblance to Scorpio, the next constellation along the zodiac from Sagittarius. Its posture and positioning are wrong—we’ll look more closely into the implications of this in a moment—but it’s there and it is overlapped by the tail end of the constellation that we recognize as Scorpio today.

Secondly, there’s the large bird above and to the right of the vulture with the curved body of a serpent nestled close to it. These two figures are in the correct position and the correct relationship to one another to match the constellation we call Ophiuchus, the serpent holder, and the serpent constellation, Serpens, that Ophiuchus holds.

Thirdly, immediately to the right of the extended front wing of the vulture there’s that other bird, smaller, like a chick, with a hooked beak. I email Burley about this, and about the different position and orientation of the scorpion on the pillar and the modern constellation of Scorpio, and we arrive, after some back and forth, at a solution. Constellation boundaries, as the reader will recall, are not necessarily drawn in the same place by all cultures at all periods and it’s clear that there’s been a shift over time in the constellation boundaries here. The chick on Pillar 43 appears to have formed a small constellation of its own in the minds of the Göbekli Tepe astronomers—a constellation that utilized some of the important stars today considered to be part of Scorpio. The chick’s hooked beak is correctly positioned, and its body is the correct shape, to match the head and claws of Scorpio. ….

Fourthly, beside the scorpion on Pillar 43 is a serpent and beneath the scorpion are the head and long neck of yet another bird, with a headless anthropomorphic figure positioned to its right. The serpent matches the tail of Sagittarius (as we’ve seen, the vulture appears to be composed from the central part of Sagittarius only—the Teapot—so this leaves the remainder of the constellation available to the ancients for other uses). The best contenders for the bird, and for the peculiar little anthropomorphic figure to its right are parts of the constellations we know today as Pavo and Triangulum Australe. The remainder of Pavo may be involved with further figures present on the pillar to the left of the bird.

As is the case with Sagittarius, elements of the modern constellation of Scorpio have been redeployed in the ancient constellations depicted on Pillar 43. Only the tail of our Scorpio is in the correct location to match the scorpion on Pillar 43 and its head faces to the right, whereas the head of the scorpion on the pillar faces to the left.

The scorpion on the pillar is also below the vulture, whereas modern Scorpio is a very large constellation lying parallel and to the right of Sagittarius.

I suggest the solution to this problem is that the scorpion on Pillar 43 is conjured from a combination of the tail of the modern constellation of Scorpio (right legs of the Pillar 43 scorpion), an unused part of the “Teapot” asterism of Sagittarius (right claw of the Pillar 43 scorpion) and the constellations that we know as Ara, Telescopium and Corona Australis (respectively the tail, left legs and left claw of the Pillar 43 scorpion). Meanwhile, as noted above, the claws and head of the modern constellation of Scorpio have been co-opted to form the chick with the hooked beak on Pillar 43.

This whole issue of the relationship between the modern constellations of Scorpio and Sagittarius and the scorpion and vulture figures depicted on Pillar 43 takes on a new level of significance when we remember that in some ancient astronomical figures Sagittarius is depicted not only as a centaur—a man-horse—but also as a man-horse hybrid with the tail of a scorpion, and sometimes simply as a man-scorpion hybrid. …. On Babylonian Kudurru stones (often referred to as boundary stones, although it is likely that their function has been misunderstood …) a figure of a man-scorpion drawing a bow frequently appears that “is universally identified with the archer Sagittarius.” …. What further cements the identification of Sagittarius with the vulture on Pillar 43 is that these man-scorpion figures from the Babylonian Kudurru stones are very often depicted with the legs and feet of birds. …. Moreover, in some representations a second scorpion appears beneath the body—i.e. beneath the Teapot asterism—of Sagittarius … reminiscent of the position of the scorpion on Pillar 43 (see Figures 50 and 51).

Figure 51: Man-scorpion Sagittarius figures from Bablylonian Kudurru stones (left) are frequently depicted with the legs and feet of birds, further strengthening the identification of the vulture figure on Pillar 43 with Sagittarius. In other Mesopotamian representations (right) we see a second scorpion beneath the body of Sagittarius occupying a similar position to the scorpion on Pillar 43.

….

When all this is taken together it goes, in my opinion, far beyond anything that can be explained away as mere “coincidence.” The implication is that ideas of how certain constellations should be depicted that were expressed at Göbekli Tepe almost 12,000 years ago [sic], including the notion that there should be a scorpion in this region of the heavens, were passed down, undergoing some changes in the process, but nonetheless surviving in recognizable form for millennia to find related expression in much later Babylonian astronomical iconography. But given the close connections with ancient Mesopotamia, its antediluvian cities, its Seven Sages and its flood survivors washed up in their Ark near Göbekli Tepe, we should perhaps not be too surprised.

No comments:

Post a Comment